Four Freedoms Campaign

Introduction

On December 8th, 1941, one day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S.A. joined the Allies in their fight against fascism. However, the battle for the American public opinion started at an earlier time and would continue after it. It was necessary that American public opinion perceived the war as an historic necessity; and the National-Socialist regime, the most aberrant manifestation of European fascism, as a threat for the system of individual and institutional freedoms of the United States. This is the origin of the Four Freedoms campaign designed and carried out by the Roosevelt administration.

The first time Roosevelt referred to the freedom of speech, the freedom from want, the freedom of worship and the freedom from fear, the four chapters of the legendary series, was in June 1941, on occasion of the 77th presidential address to the congress of the United States. The Four Freedoms were the heart of a discourse destined to gain congress support for the military involvement in Europe:

In future days, which we seek to make secure, we look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms.

The first is freedom of speech and expression – everywhere in the world.

The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way – everywhere in the world.

The third is freedom from Want – which, translated into world terms, means economic understanding which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants – everywhere in the world.

The forth is freedom from fear – which, translated into world terms, means world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point and in such thorough fashion that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor – anywhere in the world. (Roosevelt, 1951, p.314)

Three months later, in September 1941, Roosevelt together with Winston Churchill signed the Atlantic Charter. Both leaders wrote a document to state the principles of a global war against fascism. It was another step in a process that had started in March 1941 with the Lend-Lease Act, through which the U.S. Federal Government established a program that allowed the U.S.A. to provide the Allies with war materials (Roosevelt, 1951, p.314). Yet, the country remained neutral until the Pearl Harbor attack.

The Office of War Information (OWI)

The Office of War Information (OWI) was the communication organ of the American administration during World War II. The director of the communication endeavors was Elmer Davis, a well known journalist at the time. The Office of War Information was created following the model of the Committee for Public Information (CPI) that oversaw and managed the communication strategies during World War I, and in which Edward L. Bernays had also cooperated, by the way. The experience of the CPI, in spite of the controversy generated by its role during the Paris Peace Conference at the end of the war, showed the importance of an intensive and solid communication policy in times of war. When the whole is in danger, information is the best instrument to maintain the cohesion of society and to keep high the morale of the citizenship. For any cause is lost if it lacks public support.

In 1942, the Office of War Information released a booklet entitled The United Nations’ Fight for the Four Freedoms: The Roots of All Men Everywhere. The document was written in a clean, dynamic and passionate style. The contents were carefully thought through and ordered to appeal to the deepest feelings of the citizenship and incite reflection. However, the Four Freedoms booklet was hardly effective because few people actually read it. A survey carried out by the OWI in 1942 showed that only one out of three Americans had some notions of what the Four Freedoms were and where they came from. According to the same assessment, no more than 2% of the American population was able to correctly identify which the four freedoms of the campaign were (Hennessey & Knutson, 1999, p.147).

To reinforce the effect of the booklet, the OWI also designed a series of advertisements and produced some films about the Four Freedoms. It was in vain. Accountable for the communication fiasco was the OWI, which, by the president’s decision, had all authority in publicity and communication matters. Still, many of the OWI members were not communication professionals. Liberal intellectuals became involved in the activities of the office and sometimes they clashed because of their particular way of thinking and different methods with the professional communicators. This heterogeneity of the OWI might explain its lack of success to make the Four Freedoms popular. At that moment Normal Rockwell decided to help out.

Norman Rockwell: The Most American of all American Artists

In 1942 at the peak of his professional activity, Norman Rockwell had the idea of visualizing Roosevelt’s Four Freedom so that the American public could better comprehend and assimilate the message. Rockwell, unlike most of the artists of the 20th century, was very popular among the people. His covers for the Saturday Evening Post, Boy Scout calendars and numerous advertisements contributed to make him extremely well-liked. These activities also explain why Rockwell never enjoyed much respect in the circles of Art and Culture, both concepts written with capitals. At a time at which Art had become pure rhetoric, i.e. when the control over the word had replaced the virtuosity of the craftsmanship, and the concept had shifted the actual work of art, Rockwell’s hyperrealist style put him outside the trends established by the art gurus. Rockwell was, in spite of his popularity – or perhaps because of it – an unappreciated artist.

Still, Rockwell’s work possesses a very particular artistic depth. His pictures seem to be able to capture the elusive passing of time, to freeze for eternity a chunk of the life of the everyday characters that inhabit Rockwell’s artistic world. The most American of all American artists was also able to visualize and pay tribute to the values of his fellow countrymen. The spontaneity of Norman Rockwell’s daily scenes is only apparent, though. His compositions result from a deeply elaborated, and – in the best sense of the word – theatrical scenery. Every element incorporated into the picture has an expressive function and contributes to the effect of the whole.

Rockwell’s reception in the art circuits proves, again, that there is a prevailing discourse that determines who is going to be regarded as Artist, again with capital A, and who will be excluded from this particular Olympus, regardless of the intrinsic value of their work. Rockwell’s style represented an affront against the artistic mainstream of his time. The lack of intellectual recognition never seemed to bother the artist, though, which is probably the ultimate proof of his size as a true artist.

Four Freedoms Campaign – Timeline

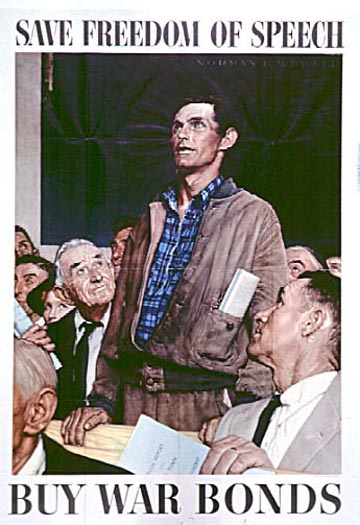

An actual event inspired Norman Rockwell to translate Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms into images. In the small town the painter was living in, Arlington, Vermont, a man named Jim Edgerton stood up in one of the town meetings to express an opinion that obviously was against the way of thinking and feeling of his neighbors. Although most of the attendants to the meeting disagreed with what Mr. Edgerton was saying, they listened to him and showed respect toward the act of expressing opinion against the majority (Rockwell, 1960. p.339). This relatively insignificant episode impressed Rockwell, always very sensitive to the values of his fellow Americans, and extremely clever when it came to emotionally connect with them.

Rockwell very soon became conscious that it was necessary to intensify this emotional connection and, at the same time, to reduce the complexity of the messages generated by the OWI. He later admitted having been unable to read further than the first paragraph of the Atlantic Charter, the document against the fascism signed by Churchill and Roosevelt. The OWI had been trying to give publicity to the document through radio and press, but its content was never absorbed by the broad public. Rockwell asked his friends and acquaintances about their experiences with the Charter and found out that nobody had been able to pass the fateful first paragraph (Rockwell, 1960. p.341). It was obvious that the informative efforts and ideals of the OWI were evaporating without having the expected effect. Thus, his idea was to “take them [the ideals of the Four Freedoms] out of the noble language of the proclamation and put them in terms everybody can understand” (Rockwell, 1960. p.340).

Nobody had to teach Rockwell the superior power of the image to convey simple ideas and help connect with the people. This was actually his job before the war started – and he did it superbly. His experience as an illustrator provided him with the certainty of the expressive potential of the image. Rockwell convinced Mead Schaeffer, a fellow illustrator, to travel to Washington and offer their free service to the OWI. The answer, according to Rockwell, was cordial. Nobody rejected their ideas and everybody seemed to like their pictures. However, the administrators in charge were reluctant to use them for their campaigns (Rockwell, 1960. p.339).

This is the reason why Norman Rockwell’s series of the Four Freedoms first appeared published in the Saturday Evening Post, a private institution. Ben Hibbs, the chief editor of the Post, had been working with Rockwell for several years and knew his talent perfectly. He immediately recognized the potential of the idea. The Saturday Evening Post finally ran the pictures, which appeared in four consecutive editions of the magazine on February 20th and 27th and March 6th and 13th of 1943 with the title: “Number _ in a Series Depicting the Four Freedoms for Which We Fight”. The pictures were complemented with a text written by four very well-known authors at the time: Will Durant, Booth Tarkington, Carlos Bulosan, and Stephen Vincent Benét (Olson, 1983, p.16). Ben Hibbs pointed out how delicate the time was in which the pictures were given to the press: “they appeared right a time when the war was going against us on the battle fronts, and the American people needed the inspirational message which they conveyed so forcefully and so beautiful” (Rockwell, 1960. p.336).

Hibbs succeeded in persuading the Treasury Department to co-sponsor together with the Saturday Evening Post an intensive War Loan Drive to raise money to back the tremendous war effort. “Keep the Light of Freedom Burning” was the title of the tour. For practically one year, from April 28th 1943 to March 8th 1944, Rockwell’s pictures, the centerpiece of the event, were circulating through 16 major cities across the country. Always around the pictures and the idea of the Four Freedoms, the cities organized rallies, parades, work shops, raffles, performances and exhibits. The events were usually hosted by show business celebrities and community leaders. Popular war heroes were invited, as well.

Individuals who bought war bonds – this was the main goal of the tour, to sell bonds – were rewarded with prints of the Four Freedoms, as well as commemorative folders decorated with the picture “Freedom of Speech”. In addition, the bond purchasers had the honor to sign the so-called Freedom Scroll, a document that would later be handed to Roosevelt to show him the commitment of the American people to the Four Freedoms cause that the president had initiated (Murray & McCabe, 1993, p.87). The outcomes of the War Loan Drive were, indeed, spectacular. More than 1,220,000 people bought war bonds. The final collection added up to $132, 882, 593 (Rockwell, 1960. p.339).

The Sophistication of Simplicity: Rhetorical Analysis of the Four Freedoms

Olson (1983, p.16) points out that the simplicity of the images that constitute the Four Freedoms series actually contains a big amount of ambiguity. In fact, the simplicity is just apparent, for the messages conveyed through the pictures are quite sophisticated. What first calls the attention of the modern rhetorician is that there are no negative cues portrayed in the pictures. Rockwell’s art never intended to stir up hatred or to demonize determined countries or people. The Four Freedoms rather focus on positive values. They praise the American political and social system without explicitly blaming the enemy. In spite of that, the whole campaign had an unequivocal persuasive character. The final goal, as already mentioned, was to collect money and to move American public opinion to support in any way the war endeavor, even if this support was necessarily going to bring sacrifice and victims.

Born in New York in 1894, Norman Rockwell moved to Arlington, Vermont, in 1939. The life in this small town, in sheer contrast to the bustling activity of the metropolis he came from, and the plain people who inhabited it seemed to Rockwell the perfect incarnation of all the virtues he thought characteristic of the American society (Murray & McCabe, 1993, p.78). The spirit of this rural and plain America animated the Four Freedoms. Rockwell started working with his neighbors in mind and also with the confidence that “most people reasoned through concrete images far more often and effectively than through abstract principles” (Claridge, 2001, p308).

Norman Rockwell combined in the Four Freedoms series his fine flair to seize the social reality around him and the invisible network of values that give cohesion to any social form or group with his refined hyperrealist technique. Rockwell’s talent for the smallest details and nuances gave his pictures a great narrative potential. Any of his pictures, not just those of the four Freedoms series, had the power to tell a whole story. The photographic fidelity of Rockwell’s images, as already mentioned, can mislead us, for the perceived spontaneity is just illusion.

In the picture Freedom of Speech, for instance, Lester C. Olson (1983)distinguishes up to seven symbols of different key institutions of the political and social American life or its fundamental values: The church, the work ethic, the educational and  judicial system, the democratic political process, the community, and the family. Most of the people attending the meeting are clearly identified as white collars. They are, at the same time, those who are listening to the main character of the picture (Murray & McCabe, 1993). White collar and tie were, on the one hand, the official attire of holydays and religious services and celebrations. On the other hand, the white collar was – and it still is – a symbol of higher social and professional status, too, of people who do not have to earn their bread with handwork (Olson, 1883). The speaker stands up in a dignified pose. He wears a blue shirt, but this is not the only clue Rockwell gives us about his modest social rank. His hands, dark and rough, and his worn out coat reveal that we are contemplating the personification of the blue collar. The event is a town meeting, as we can read in the pamphlets of some of the attendants. It seems to take place in a school room. The direct reference to the educational system is the blackboard in the background. Still, the pews where the town neighbors are sitting are characteristics of churches and courtrooms (Olson, 1883). The whole scene transmits an idyllic – and also somewhat anachronistic – view of direct democracy. On the foreground, Rockwell shows us the hand of one of the white collar neighbors with a wedding ring. Thus, the institution of family is also suggested in the scene of democracy live. In the town meeting we can identify different types and characters: young and old people, male and female attendants, so that everybody can theoretically identify him or herself with one of the characters of the picture.

judicial system, the democratic political process, the community, and the family. Most of the people attending the meeting are clearly identified as white collars. They are, at the same time, those who are listening to the main character of the picture (Murray & McCabe, 1993). White collar and tie were, on the one hand, the official attire of holydays and religious services and celebrations. On the other hand, the white collar was – and it still is – a symbol of higher social and professional status, too, of people who do not have to earn their bread with handwork (Olson, 1883). The speaker stands up in a dignified pose. He wears a blue shirt, but this is not the only clue Rockwell gives us about his modest social rank. His hands, dark and rough, and his worn out coat reveal that we are contemplating the personification of the blue collar. The event is a town meeting, as we can read in the pamphlets of some of the attendants. It seems to take place in a school room. The direct reference to the educational system is the blackboard in the background. Still, the pews where the town neighbors are sitting are characteristics of churches and courtrooms (Olson, 1883). The whole scene transmits an idyllic – and also somewhat anachronistic – view of direct democracy. On the foreground, Rockwell shows us the hand of one of the white collar neighbors with a wedding ring. Thus, the institution of family is also suggested in the scene of democracy live. In the town meeting we can identify different types and characters: young and old people, male and female attendants, so that everybody can theoretically identify him or herself with one of the characters of the picture.

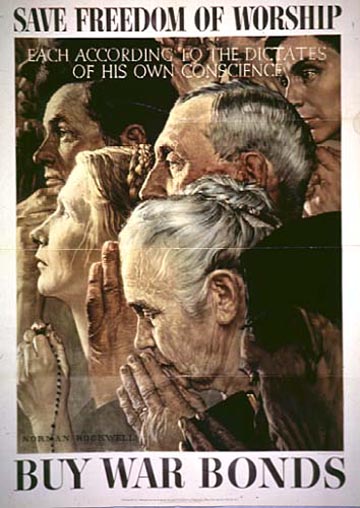

The issue of Freedom of Worship is, without doubt, the most delicate of the four items. Therefore, it does not surprise that the picture dedicated to this freedom is the most ambiguous of the series, too. The thematic ambiguity is masterfully suggested through the sepia hue and the illumination of the whole picture. The challenge of the Freedom of Worship was to portray the elements all religions practiced in the U.S. have in common without excluding any group or adding elements that might have offended the sensitivity of any of those groups. The picture, again, is rich in details. We can identify catholic symbols (Rosary), Jewish (Yarmulke) and Greek Orthodox (Olson, 1983). This is the only Picture of the series in which African-Americans (black people) appear. Still, the two black characters of the scene are portrayed in an almost marginal way, removed from the focal point at the top and at the bottom of the scene, for the Saturday Evening Post “had not yet made a practice of moving blacks into prominent visual positions” (Claridge, 2001. p.310). Besides the appeal to the religious feelings of the American population, Rockwell emphasizes, faithful to Roosevelt’s spirit, the virtue of a non-confessional state, not tied to any religious group, idea or dogma and, at the same time, tolerant with all the creeds and ethnical groups. Again, the political message is clearly suggested in a scene of religious fervor.

picture. The challenge of the Freedom of Worship was to portray the elements all religions practiced in the U.S. have in common without excluding any group or adding elements that might have offended the sensitivity of any of those groups. The picture, again, is rich in details. We can identify catholic symbols (Rosary), Jewish (Yarmulke) and Greek Orthodox (Olson, 1983). This is the only Picture of the series in which African-Americans (black people) appear. Still, the two black characters of the scene are portrayed in an almost marginal way, removed from the focal point at the top and at the bottom of the scene, for the Saturday Evening Post “had not yet made a practice of moving blacks into prominent visual positions” (Claridge, 2001. p.310). Besides the appeal to the religious feelings of the American population, Rockwell emphasizes, faithful to Roosevelt’s spirit, the virtue of a non-confessional state, not tied to any religious group, idea or dogma and, at the same time, tolerant with all the creeds and ethnical groups. Again, the political message is clearly suggested in a scene of religious fervor.

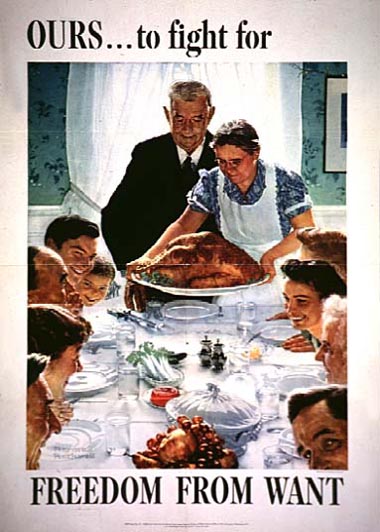

The next freedom, the Freedom from Want, another stunt of theatricality and dynamism, is introduced by one of the marginal characters at the bottom of the picture, who visually connects with the viewer and seems to invite us to  participate in the scene. The motive is the American celebration per se, Thanksgiving. The institution of family had been present in the previous pictures. Rockwell’s compositions always give visual relevance to some hands wearing wedding rings. Still, it is in the Freedom from Want where the theme of the family, as one of the pillars of the American social building, becomes a major one in the series. The familiar setting of the scene, as stated by Murray and McCabe, “elicits warmest memories of the turkey, the grandparents, and the family around the table” (Murray &

participate in the scene. The motive is the American celebration per se, Thanksgiving. The institution of family had been present in the previous pictures. Rockwell’s compositions always give visual relevance to some hands wearing wedding rings. Still, it is in the Freedom from Want where the theme of the family, as one of the pillars of the American social building, becomes a major one in the series. The familiar setting of the scene, as stated by Murray and McCabe, “elicits warmest memories of the turkey, the grandparents, and the family around the table” (Murray &

McCabe, 1993, p.343). No other celebration can match the power of Thanksgiving to amalgamate family, country and religion in a whole, which has the flavor, as Robert Bellah stated, of a “civil religion” (Bellah, 1967, p.11).

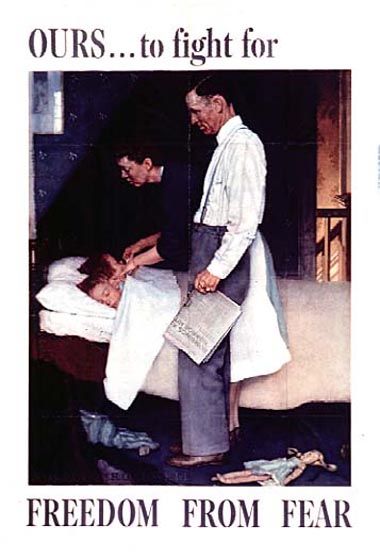

The last image of the series, Freedom fom Fear, is the only one in which we find an explicit reference to the war. In spite of the explicitness, it is an ambiguous reference, too, for no country, place or government is mentioned. The father of the family, when kissing good night to his children, holds in his  hands a newspaper with a headline about the bombing of an unidentified town. The newspaper here is a symbol of education, of literacy, and by extension, of a civilized world. This is the only picture of the series in which Rockwell suggests that this civilized world is in danger, threatened by a new form of barbarism that might annihilate the values represented by the Four Freedoms. The family becomes, also in this picture, a major theme. In this case, the family is not presented as the natural environment for happiness and celebrations, but as the last redoubt of safety, above all for those who most need this safety: the children. A couple of toys scattered across the floor show clearly the cause of the tiredness of those children who are now sleeping without the worries and anxieties that are evident in the attitude of their parents. The general public also becomes aware, as suggested by Murray and McCabe (1993), of the contrast between the safety the children are enjoying in Rockwell’s scene and those living in the town that were suffering the air-raids the newspaper is informing about.

hands a newspaper with a headline about the bombing of an unidentified town. The newspaper here is a symbol of education, of literacy, and by extension, of a civilized world. This is the only picture of the series in which Rockwell suggests that this civilized world is in danger, threatened by a new form of barbarism that might annihilate the values represented by the Four Freedoms. The family becomes, also in this picture, a major theme. In this case, the family is not presented as the natural environment for happiness and celebrations, but as the last redoubt of safety, above all for those who most need this safety: the children. A couple of toys scattered across the floor show clearly the cause of the tiredness of those children who are now sleeping without the worries and anxieties that are evident in the attitude of their parents. The general public also becomes aware, as suggested by Murray and McCabe (1993), of the contrast between the safety the children are enjoying in Rockwell’s scene and those living in the town that were suffering the air-raids the newspaper is informing about.

Verbal versus Visual Messages

Rockwell’s pictures, as already stated, avoided any direct reference to the enemy, the German government or the countries belonging to the Axis. The Four Freedoms were conceived to exalt the virtue of American traditional values. The enemy calls the attention, primarily, due to its absence. For instance in the Freedom of Worship, Rockwell avoids portraying characters with Arian, Asian or Italian features, the three major ethnics groups united by the Axis.

A direct reference to these countries and their governments or political standpoints appears in the texts attached to the pictures. Although they were written by different authors, the four texts followed the same structure and showed a very similar style. They started with the praise of the characteristic American freedoms portrayed in Rockwell’s illustrations. In contrast to these freedoms, they depicted the tyranny and the barbarism into which fascism had degenerated. The texts ended in a final appeal to the solidarity of all Americans and a dramatic call for sacrifice (Olson, 1983).

In the texts, in contrast to the illustrations, the threat was expressed with no ambiguity. Perhaps the best example is the writing attached to the Freedom from Want, signed by Carlos Bulosan:

The totalitarian nations hate democracy. They hate us because we ask for a definite guaranty of freedom of religion, freedom of expression, and freedom from fear and want. Our challenge to tyranny is the depth of our faith in a democracy worth defending. (as cited in Olson, 1983, p.21)

The Four Freedoms Tour

Of course, the Four Freedoms campaign was not the only activity organized by the OWI, but most of its informative and persuasive efforts were articulated by Roosevelt’s idea. The OWI created a division of journalist and literary authors who wrote all of the propaganda pieces that came out of its headquarters. One of those pieces was a pamphlet entitled The United Nations Fight for the Four Freedoms. Hollywood film industry also collaborated with the OWI. Numerous movies were released with the war as background and ardent patriotic messages. The movies, strongly publicized and broadly circulated, were supposed to reach approximately 85,000 Americans every week (Murray & McCabe, 1993). Also the existing mass media generously supported the campaign giving free air time or advertising space to the propaganda pieces of the OWI (Murray & McCabe, 1993). In several broadcast programs and film showings, the public was asked to buy war bonds. Many celebrities lent their charisma to the war effort. Above all, the beloved movie stars used to appear in the events organized by the OWI. Perhaps the most popular endorsement was Bing Crosby singing Buy, Buy, Buy, Buy a Bond! The popular comic heroes, such as Batman, Spiderman, the Masked Marvel, Secret Agent X-O, Spy Smasher, even the cowboy Tom Mix, supported the OWI in its fight against the Nazis (Murray & McCabe, 1993).

Yet, the most effective campaign of the OWI was based on the idea of the Four Freedoms. The OWI organized a tour all over the country, the already mentioned War Loan Drive, to show Rockwell’s pictures. A strong publicity campaign preceded the arrival of the convoy. Most of the U.S. media participated in the promotion of the campaign, but it was the Saturday Evening Post, of course, the most constant of them. The OWI helped the media of the area by sending them press releases in the days prior to the exhibition, so that they could offer to their readers first hand information about it. Parallel to the display of Rockwell’s Four Freedoms, a series of events were arranged. Rallies, contests, educational programs, parades, or demonstrations against the war or the Axis countries helped to attract the attention toward the exhibition and the fund raising event.

The radio intensively promoted the tour, too. Over 90 broadcast programs were dedicated to the itinerant exposition. Some of them were live broadcasts of the manifestations organized to celebrate the arrival of Rockwell’s illustrations. For almost one year, the Drive absorbed the attention of radio news. Altogether, 19,425 messages were broadcasted that reached 31 million homes (Murray & McCabe, 1993).

The exhibitions became a form of pseudo-event that generated lots of news. Hundreds of feature stories about anecdotes, incidents and personal experiences related to the tour were published and translated into more than 30 languages to facilitate the international distribution. Thus, the Four Freedoms became a pioneer in the field of international public relations, too. Documentary movies about the exhibition, as well as portraying the artist, Norman Rockwell, in action, were shown in more than 15,000 movie theaters. All of a sudden, the images of the Four Freedoms were everywhere; in churches, cabs, milk bottles, bank statements or gas receipts (Murray & McCabe, 1993).

Norman Rockwell became himself an icon of the American popular culture, which was, to some extent, a consequence of the intensive propaganda. The origin of the myth Norman Rockwell is, again, the Saturday Evening Post. On February 13th, 1943, a feature story about the artist appeared in the paper. Rockwell was depicted in the article as the archetype of the “common man”, an oversimplification given his immeasurable talent (Murray & McCabe, 1993). The wave of popular idolatry was overwhelming. It reached the climax when Rockwell was signing reprints of his Four Freedoms at Hetch’s Department Store. Totally amazed, the artist witnessed how “women in the crowd were fainting; a lady’s petticoat dropped around her ankles as she was standing before me …” (Rockwell, 1960).

Of course, the actual objective of the tour was to sell war bonds, and this was also the highlight of the exhibitions. Every bond purchaser automatically received a full color set of the four illustrations (Murray & McCabe, 1993). The money went entirely to the Treasury funds, for the Saturday Evening Post had authorized the OWI to use and reprint Rockwell’s images.

At the end of the tour, more than 1,200,000 people had attended the exhibitions of the Four Freedoms. To satisfy the tremendous demand – over 2,000 copies were requested every day due to the sale of war bonds – the OWI finally printed 4 million copies (Rockwell, 1960).

Conclusions

In 1947, two years after the end of World War II, a second Four Freedoms tour was arranged, this time with a nostalgic rather than combative character. In this second tour, Rockwell’s pictures traveled by train through 326 cities. The popular response was, again, and after the danger was apparently gone, spectacular. The Four Freedoms attracted more than 3.5 million people.

Franklin D. Roosevelt created the message of the Four Freedoms to morally justify his war policy. He was aware that to join the Allies would represent for the American people a colossal sacrifice. To secure their support, it was necessary to build an emotional connection with the public. Roosevelt was aware that there was no need to enlighten public opinion about the mysteries of war, diplomacy or international law. In spite of the strong emotional charge of the Roosevelt’s original address, the message did not fully reached the broad mass of people. And the president knew that it was essential for the success of his enterprise to implant the spirit of the Four Freedoms in the American public opinion before the moment came to ask his fellow countrymen for the ultimate sacrifice.

This was exactly the function of Rockwell’s pictures. And to judge by the results, nobody would doubt that they were extraordinarily effective. President Roosevelt himself acknowledged it in one of the letters he sent to the painter:

You have done a superb job in bringing home to the plain, everyday citizen the plain, everyday truths behind the four freedoms. (Hennessey &e Knutson, 1999, p.130)

Also the Treasury Secretary, Henry Morgenthau, who was initially reluctant to accept Rockwell’s aid, ended up recognizing the effectiveness of the Four Freedoms illustrations:

NR’s paintings, the 4F are dramatic illustrations of the principles for which we fight. The number of E-bonds sold proves the success of the show in reaching the average citizen. (Murray & McCabe, 1993, p.91)

In view of the success of the series, other branches of the U.S. federal government tried to persuade Rockwell to support their efforts to raise money. The artist created other posters, always aimed to sell war bonds, which never matched the popularity of the Four Freedoms. However, he refused to work for other federal agencies. For instance, Rockwell denied cooperation to the Alcohol Tax Unit when he was asked to visually illustrated messages about the personal tragedies that could be caused by the practice of not rendering “dangerous war souvenirs” (letters to Norman Rockwell).

Roosevelt and Rockwell’s decision of focusing on positive traditional values inherent to the American culture and not stirring up hatred against other countries, political systems or ethnic groups is the reason why the Four Freedoms are now one of the most reproduced artworks of all times. This strategic decision is the secret of their effectiveness, and further the explanation of why the images were useful in international public relations. Despite the passing of years, and despite the fact that the National-Socialism does not represent a menace any more, the Four Freedoms still appeal to the heart and conscience of the American people. They remain symbols not of what the country is, but of what the country ought to be.

References:

- Bellah, R. N. (1967). Civil Religión in America. Daedalus, 96.

- Claridge, L. (2001). Norman Rockwell: A Life. New York: Random House.

- Goodrum, C. & Dalrymple, H. (1990). Advertising in American: The First 200 Years. New York: Harry N Abrams, Inc., Publishers.

- Hennessey, M. H. & Knutson, A. (1999). Norman Rockwell: Pictures for the American People. Seattle: Marquand Books.

- Letters to Norman Rockwell stored at the Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, MA visited 01.09.06.

- Murray, S. & McCabe, J. (1993). Norman Rockwell’s Four Freedoms: Images that Inspire a Nation. Stockbridge, MA: Berkshire House.

- Olson, L. C. (1983). Portraits in Praise of a People: A Rhetorical Analysis of Norman Rockwell’s Icons in Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms” Campaign. Quarterly Journal of Speech 69. 15-24.

- Rockwell, N. (1960). My Adventures as an Illustrator. (as told by Thomas Rockwell). Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, Inc.

- Roosevelt, F. D. (1950). Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt, vol.10 (1938-1950). Samuel Rosenman (Ed.). New York: Random House.

- Roth, P. (2004). The Plot against America. New York: Vintage Books.

- Office of War Information (1942). The United Nations’ Fight for the Four Freedoms: The Roots of All Men Everywhere. Washington, D. C.